Data Lakehouse implementations with pg_mooncake

The journey of combining OLTP (Online Transaction Processing) and OLAP (Online Analytical Processing) within a single database system has been unfolding for decades. The introduction of HTAP (Hybrid Transactional and Analytical Processing) further advanced this concept—enabling a single platform to handle both OLTP workloads (such as transactional updates and sales) and OLAP workloads (such as business intelligence and analytical queries).

Many vendors, including Oracle, IBM, Databricks, and GridGain, have developed their own HTAP solutions, each with its own strengths and limitations.

Over the past 17 years, database management systems (DBMS) have evolved significantly in response to changing user requirements. This evolution can be summarized as follows:

RDBMS → NoSQL (Key-Value Stores, Bigtable, Graph) → Distributed Databases (including In-Memory Systems) → Object Storage → Columnar Databases

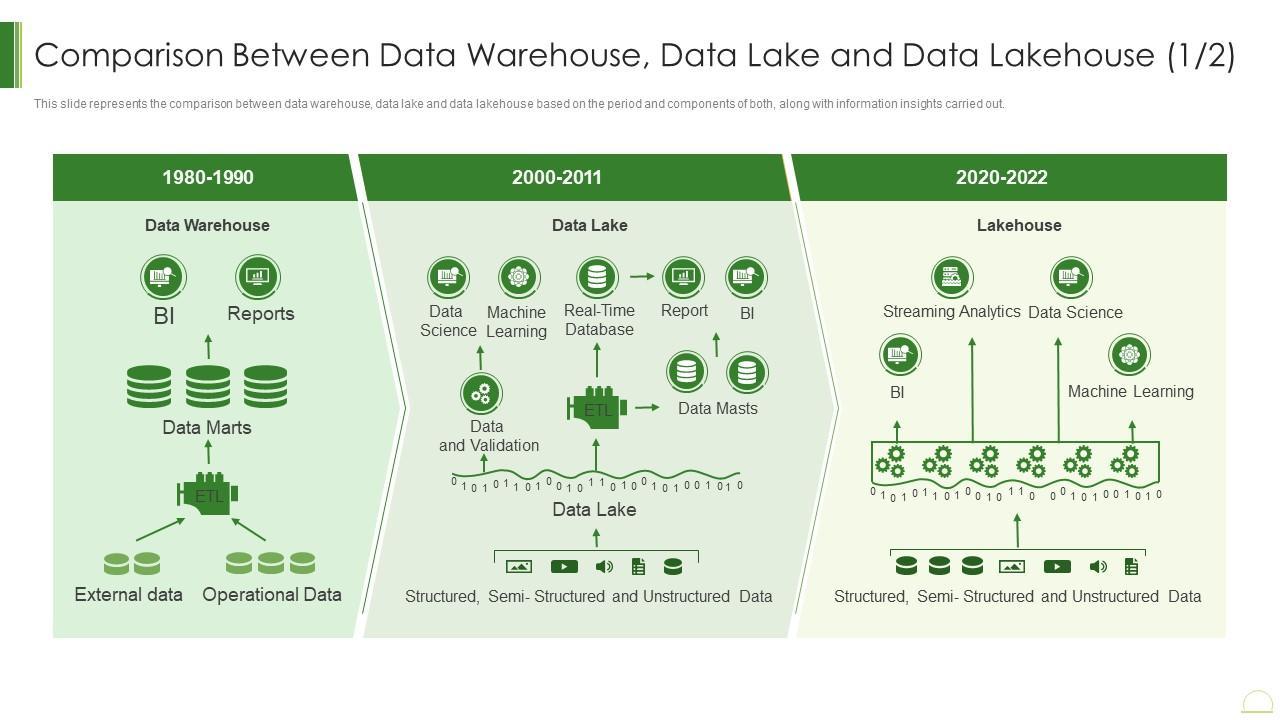

These advancements have also transformed the data storage landscape, giving rise to new architectural paradigms: Data Warehouse → Data Lake → Lakehouse.

The following fragment (sourced from an online presentation) illustrates the key differences among these three mainstream architectures.

There are plenty of articles, presentations, and podcasts available online that explore these topics in depth. However, from my point of view, the main advantage of the Lakehouse architecture over other approaches lies in its ability to combine the strengths of both data warehouses and data lakes.

Specifically, the Lakehouse architecture:

Adds a metadata layer (such as Apache Iceberg) to provide structured organization and improved data readability.

Supports ACID transactions, ensuring reliability and consistency for both analytical and transactional workloads.

Reduces ETL/ELT complexities by enabling direct access to data in its native format.

Eliminates the need for separate Data Marts or Data Masts, simplifying data availability across the organization.

In my experience, most mid-sized companies (and sometimes even enterprises) primarily need a storage system that can handle online transactions while also supporting basic business intelligence queries on that data. However, in today’s era of AI, having a dedicated analytical platform like a Data Lake or Data Lakehouse is highly beneficial. Unfortunately, not every company can afford to build and maintain such a platform.

To address the analytical needs of small and mid-sized businesses, several efforts have been made to combine OLTP and OLAP capabilities within a single RDBMS. One of the earlier attempts was cstore_fdw, which is now part of Citus. More recently, the open-source community has introduced another promising solution — Mooncake, an extension for PostgreSQL. Although still in an experimental stage, Mooncake shows great potential.

In this blog post, I’ll walk through the entire learning journey of this solution — its architecture, how it works under the hood with the storage system, and its query performance.

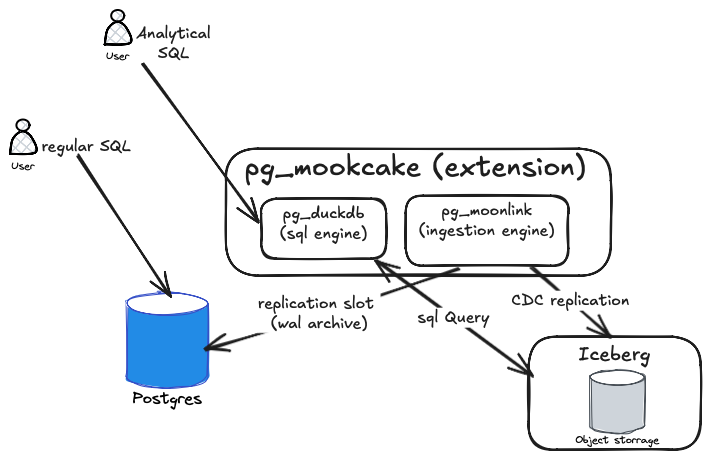

Disclaimer: This post reflects my personal learning experience. Over the past few years, I’ve explored several data replication systems such as Oracle GoldenGate, application-level replication, event-sourcing replication, and more recently, CDC (Change Data Capture) replication. Exploring new technologies like this helps me continue evaluating and expanding my understanding in this field.The Mooncake project (or pg_mooncake) is a PostgreSQL extension designed to enhance analytical capabilities by adding columnar storage and vectorized execution. The project is primarily powered by two supporting extensions: pg_moonlink and pg_duckdb.

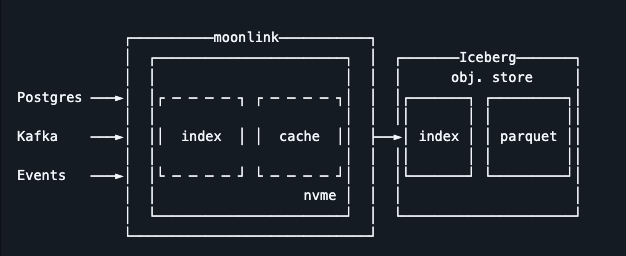

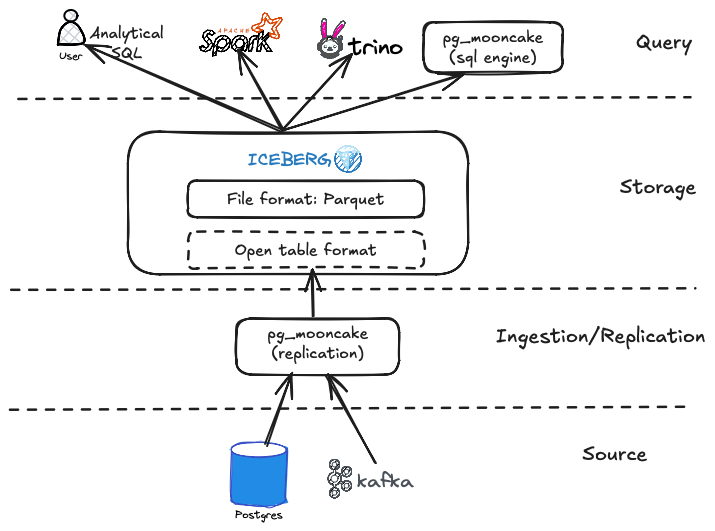

pg_moonlink - It is an Iceberg-native data ingestion engine that can replicate data directly into Lakehouse storage. Iceberg provides an open table format for managing data in the Lakehouse, typically using columnar file formats such as Parquet. The main advantage of this extension is that it eliminates the need for additional components like Debezium or Kafka to replicate data into the Lakehouse.

pg_duckdb - It enables DuckDB’s columnar and vectorized analytics engine inside PostgreSQL, providing high-performance data analytics. Out of the box, it allows executing analytical queries without any code changes. It can also read and write data from various formats such as Parquet, CSV, JSON, Iceberg, and Delta Lake, across storage systems like S3, GCS, Azure, and Cloudflare R2.

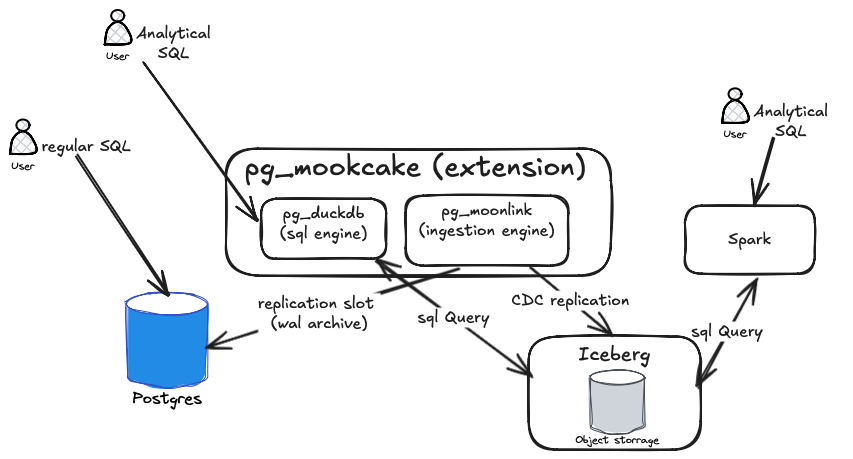

In this solution, you can also query data directly from Iceberg storage without relying on pg_duckdb. You can use a pre-installed SparkSQL or any other SQL engine for data analysis instead (as shown in the next diagram).

Note that pg_mooncake runs as a worker when used as a PostgreSQL extension. However, in production, you can also install and deploy it as a standalone application.Now that we have an overview of the pg_mooncake architecture, let’s design a simplified version of a data lakehouse architecture.

There are two ways to use pg_mooncake:

Use a single PostgreSQL database with

pg_mooncakefor both OLAP and OLTP workloads.Integrate

pg_mooncakeas part of a data lakehouse analytical platform.

So far, we’ve explored the features and possibilities of pg_mooncake. I believe this is the perfect time to get hands-on and see how it works in practice. For simplicity, I will use a self-managed Docker container running PostgreSQL with the pg_mooncake extension preinstalled.

In the rest of this article, we will:

Install the extension.

Create tables for storing data.

Insert test data.

Examine how data is stored in both regular tables and columnar storage.

Run SQL benchmarks and analyze query plans.

Let's start by setting up the Postgres database.

Step 1: Run the Pre-Installed pg_mooncake Extension with PostgreSQL

docker run --name mooncake --rm -e POSTGRES_PASSWORD=password mooncakelabs/pg_mooncakeIf you want to mount a local folder that will be accessible from the container, run the following command:

docker run --name mooncake --rm \

-e POSTGRES_PASSWORD=password \

-v /PATH_TO_FOLDER:/mnt/scripts \

mooncakelabs/pg_mooncake

Step 2: Open the psql CLI Inside the Docker Container

docker exec -it mooncake psql -U postgresStep 3: Create the pg_mooncake Extension

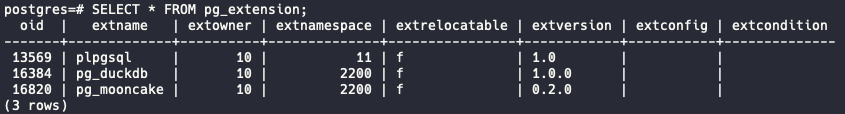

CREATE EXTENSION pg_mooncake CASCADE;Step 4: Check the Installed Extensions

SELECT * FROM pg_extension;It will return something similar as shown below:

Step 5: Create Sample Entities

For this tutorial, we’ll use well-known entities from the Oracle Tiger schema, such as Emp and Dept.

CREATE TABLE DEPT (

DEPTNO INTEGER NOT NULL,

DNAME VARCHAR(14),

LOC VARCHAR(13),

CONSTRAINT DEPT_PRIMARY_KEY PRIMARY KEY (DEPTNO));

CREATE TABLE EMP (

EMPNO INTEGER NOT NULL,

ENAME VARCHAR(10),

JOB VARCHAR(9),

MGR INTEGER CONSTRAINT EMP_SELF_KEY REFERENCES EMP (EMPNO),

HIREDATE VARCHAR(10),

SAL DECIMAL(7,2),

COMM DECIMAL(7,2),

DEPTNO INTEGER NOT NULL,

CONSTRAINT EMP_FOREIGN_KEY FOREIGN KEY (DEPTNO) REFERENCES DEPT (DEPTNO),

CONSTRAINT EMP_PRIMARY_KEY PRIMARY KEY (EMPNO));Step 6: Create Columnstore Mirrors

Next, we’ll create columnstore mirror tables, emp_iceberg and dept_iceberg, which will stay in sync with the emp and dept tables.

CALL mooncake.create_table('emp_iceberg', 'emp');

CALL mooncake.create_table('dept_iceberg', 'dept');These two tables will store their data locally in Parquet format within the Docker container.

Step 7: Populate Tables with Test Data

-- Insert a few departments

INSERT INTO DEPT (DEPTNO, DNAME, LOC) VALUES

(10, 'ACCOUNTING', 'NEW YORK'),

(20, 'RESEARCH', 'DALLAS'),

(30, 'SALES', 'CHICAGO'),

(40, 'OPERATIONS', 'BOSTON');

-- Populate 10,000 employees

INSERT INTO EMP (EMPNO, ENAME, JOB, MGR, HIREDATE, SAL, COMM, DEPTNO)

SELECT

gs AS empno,

'EMP' || gs AS ename,

(ARRAY['CLERK','SALESMAN','MANAGER','ANALYST','PRESIDENT'])[floor(random()*5 + 1)],

CASE WHEN gs % 10 = 0 THEN NULL ELSE floor(random() * (gs - 1) + 1) END AS mgr,

date '2010-01-01' + (random() * 5000)::int AS hiredate,

round((2000 + random() * 8000)::numeric, 2) AS sal,

round((random() * 2000)::numeric, 2) AS comm,

(ARRAY[10,20,30,40])[floor(random()*4 + 1)]

FROM generate_series(1, 10000) AS gs;

-- Optional: verify

SELECT COUNT(*) AS total_employees FROM EMP;The data should be replicated to the dept_iceberg and emp_iceberg tables accordingly. Let’s check the emp_iceberg table as follows:

select count(*) from emp_iceberg;It should return 10000 rows (1 count)

count

-------

10000

(1 row)Also, let’s check all the relationships (tables) in the database.

postgres=# \dt

List of relations

Schema | Name | Type | Owner

--------+--------------+-------+----------

public | bonus | table | postgres

public | customer | table | postgres

public | dept | table | postgres

public | dept_iceberg | table | postgres

public | dummy | table | postgres

public | emp | table | postgres

public | emp_iceberg | table | postgres

public | item | table | postgres

public | ord | table | postgres

public | price | table | postgres

public | product | table | postgres

public | salgrade | table | postgres

(12 rows)The list includes the emp, emp_iceberg, dept, and dept_iceberg tables. Note that there are also a few other tables in the schema.

Step 8: Examine the Storage System

postgres=# select pg_relation_filepath('emp');

pg_relation_filepath

----------------------

base/5/16854

(1 row)This is the physical file path of the emp table’s heap in PostgreSQL’s storage system. The path is relative to the PostgreSQL data directory ($PGDATA).

base/5/16854breaks down as:base/→ directory storing per-database tables.5/→ the database OID (internal PostgreSQL numeric ID).16854→ the relfilenode, the internal file for the table in PostgreSQL.

Now, lets check the storage for the emp_iceberg table.

postgres=# select pg_relation_filepath('emp_iceberg');

pg_relation_filepath

----------------------

base/5/16856

(1 row)The 'pg_relation_filepath' function always points to the PostgreSQL catalog entry, not Mooncake’s external storage. Mooncake uses metadata tables that map logical PostgreSQL relations to Parquet files, but PostgreSQL itself still assigns an OID under base/.

So base/5/16831 is just the PostgreSQL internal metadata file, not the actual Parquet storage.

Let’s query the Parquet storage. Open a new terminal and run the following command:

docker exec -it mooncake bash -c "ls -lR \$PGDATA/pg_mooncake | grep parquet"

-rw------- 1 postgres postgres 1426 Oct 16 13:09 data-0199ed24-1fa0-73c1-9925-943c2cb5ae71-0199ed24-2197-7de2-9257-37d6bf6a5492.parquet

-rw------- 1 postgres postgres 1426 Oct 16 09:39 ic-0199ec63-3ca3-7fa0-be2f-456b3f215e8a-0199ec63-3ca7-7b21-9ca0-d54ef16fc381.parquet

-rw------- 1 postgres postgres 313552 Oct 16 13:07 data-0199ed21-c879-78e2-a180-112ce42c00ea-0199ed21-ca6d-7891-a93c-603f5f1646d6.parquet

-rw------- 1 postgres postgres 3620 Oct 16 09:36 ic-0199ec60-e576-7be3-a2f2-ff8f1221d77e-0199ec60-e57c-7022-81f1-191c7fa434fe.parquet

-rw------- 1 postgres postgres 561573 Oct 16 13:05 inmemory_postgres.public.emp_iceberg_0_30214952.parquetAlternatively, you can run the following command from the host machine to list all Parquet files for the Mooncake tables inside the Docker container.

docker exec -it mooncake bash -c "for dir in \$PGDATA/pg_mooncake/*; do echo \"Table Dir: \$(basename \$dir)\"; ls -lh \$dir/*.parquet 2>/dev/null; echo; done"

Table Dir: initial_copy

Table Dir: moonlink_metadata_store.sqlite

Table Dir: moonlink.sock

Table Dir: postgres

Table Dir: postgres.public.dept_iceberg

Table Dir: postgres.public.emp_iceberg

Table Dir: read_through_cache

Table Dir: temp

-rw------- 1 postgres postgres 549K Oct 16 13:05 /var/lib/postgresql/data/pg_mooncake/temp/inmemory_postgres.public.emp_iceberg_0_30214952.parquet

Table Dir: _walWe can also check the total size of each table in Parquet format.

docker exec -it mooncake bash -c "du -sh \$PGDATA/pg_mooncake/*"

12K /var/lib/postgresql/data/pg_mooncake/initial_copy

12K /var/lib/postgresql/data/pg_mooncake/moonlink_metadata_store.sqlite

0 /var/lib/postgresql/data/pg_mooncake/moonlink.sock

608K /var/lib/postgresql/data/pg_mooncake/postgres

4.0K /var/lib/postgresql/data/pg_mooncake/postgres.public.dept_iceberg

4.0K /var/lib/postgresql/data/pg_mooncake/postgres.public.emp_iceberg

4.0K /var/lib/postgresql/data/pg_mooncake/read_through_cache

556K /var/lib/postgresql/data/pg_mooncake/temp

20K /var/lib/postgresql/data/pg_mooncake/_walThe size of our dept_iceberg and emp_iceberg tables is only 4 KB, while the regular emp and dept tables will be much larger. Let’s check.

postgres=# select pg_size_pretty ( pg_relation_size ( 'emp' ));

pg_size_pretty

----------------

856 kB

(1 row)856 KB is much larger than 4 KB.

Step 9: Execution Time

Now that we’ve examined the internal structure of Mooncake, it’s time to evaluate query performance.

We’ll run an advanced analytics query using window functions to rank employees by salary within each department.

SELECT e.empno,

e.ename,

e.deptno,

d.dname,

e.sal,

RANK() OVER (PARTITION BY e.deptno ORDER BY e.sal DESC) AS salary_rank

FROM emp e

JOIN dept d ON e.deptno = d.deptno

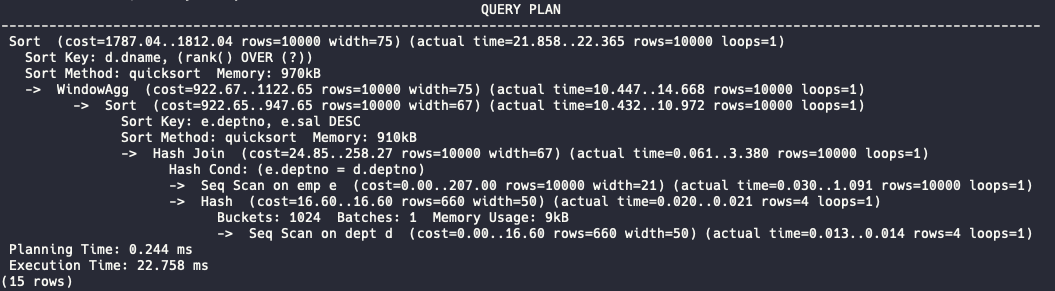

ORDER BY d.dname, salary_rank;Let’s use the EXPLAIN (ANALYZE) function to analyze the query performance.

explain (analyze) SELECT e.empno,

e.ename,

e.deptno,

d.dname,

e.sal,

RANK() OVER (PARTITION BY e.deptno ORDER BY e.sal DESC) AS salary_rank

FROM emp e

JOIN dept d ON e.deptno = d.deptno

ORDER BY d.dname, salary_rank;This should return the following query plan:

Now, let’s run the same query on the Iceberg tables.

explain (analyze) SELECT e.empno,

e.ename,

e.deptno,

d.dname,

e.sal,

RANK() OVER (PARTITION BY e.deptno ORDER BY e.sal DESC) AS salary_rank

FROM emp_iceberg e

JOIN dept_iceberg d ON e.deptno = d.deptno

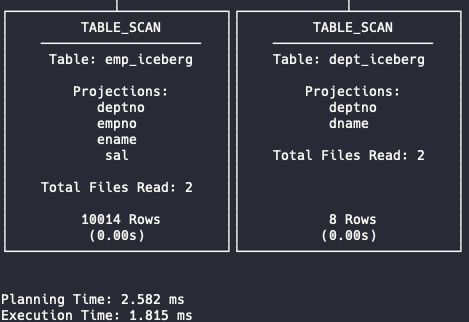

ORDER BY d.dname, salary_rank;The Mooncake EXPLAIN plan is too long to display in a single window, so here are the final fragments. In my case, the results are as shown below:

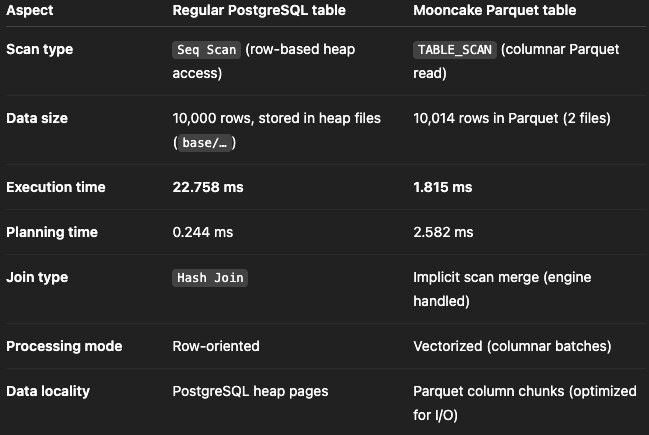

The execution time is 1.8 ms compared to 22.7 ms—a significant difference. Let’s analyze the two execution plans to understand what’s happening internally.

Parquet only reads the columns (

deptno, empno, ename, sal), skipping others which dramatically less disk I/O and memory footprint.The mooncake pg_duckdb uses a vectorized scan engine, processing thousands of rows per CPU call (SIMD-like efficiency).

Note that,

Total Files Read: 2. That means Mooncake parallelized the scan across two Parquet files.

Moreover, Parquet data is compressed (often by 4–10×) and encoded per column (e.g., dictionary encoding). So, mooncake read Less data from disk → fewer pages → lower latency.

In conclusion, pg_mooncake makes it easy to combine OLTP and OLAP in PostgreSQL. Using columnstore Iceberg tables, we drastically reduced storage size and boosted query performance.

Note: This project is still experimental and currently has the following limitations:

lake of integration with cloud storage (S3, R2) and Iceberg REST catalogs;

writing data directly into Mooncake columnstore tables, bypassing PostgreSQL storage/WAL.

Despite these limitations, pg_mooncake shows strong potential as a practical solution for efficient storage and fast analytics in data lakehouse architectures.